2024

Hua Shen

Orthopaedic Surgery

- Email: hshen22@nospam.wustl.edu

Focus: Development of effective treatments for tendon injuries and related disorders through multidisciplinary collaborations, which integrates the expertise and innovative technology in the field of translational tendon research, regenerative medicine, extracellular vesicle application, tissue engineering, and drug development.

Dr. Hua Shen is an Assistant Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery at Washington University in St. Louis. Dr. Shen’s laboratory conducts basic and translational musculoskeletal research with a particular interest in the development of biological treatments for tendon injuries. The research lab employs a multidisciplinary approach through collaborations with orthopaedic surgeons and biomedical engineers, which integrates the expertise and cutting-edge technology in regenerative medicine, tissue engineering, drug development and delivery, extracellular vesicle application, and orthopaedic research.

Focus: Development of effective treatments for tendon injuries and related disorders through multidisciplinary collaborations, which integrates the expertise and innovative technology in the field of translational tendon research, regenerative medicine, extracellular vesicle application, tissue engineering, and drug development.

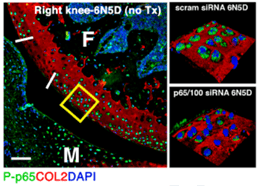

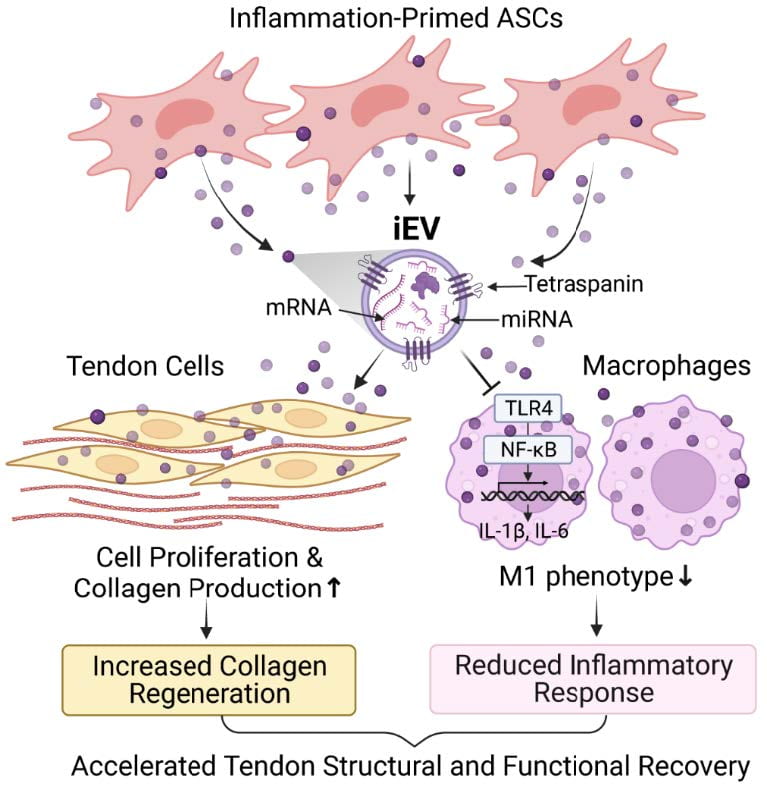

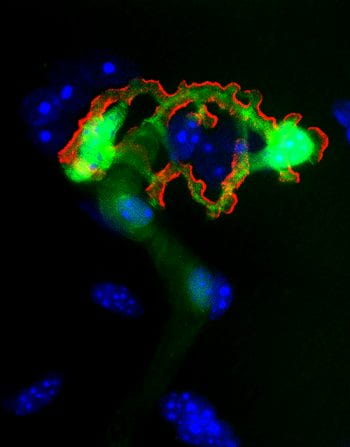

Adult tendons are pauci-cellular and have a limited ability to repair themselves after injury. Injury-induced inflammation, which causes cell death and matrix degradation and scar tissue formation, further impedes tendon structural and functional recovery after injury. The team’s earlier studies showed that adipose-derived stem cells (ASCs), either alone or in combination with such tenogenic growth factors as BMP12 and Connective Tissue Growth Factor, can potentially improve tendon healing by both attenuating tendon inflammatory response and promoting tissue regeneration. In light of the latest advancement in extracellular vesicle biology and nanotechnology, the Shen lab discovered that extracellular vesicles (EVs) produced by ASCs are superior to their parent cells as a regenerative medicine to treat tendon injury. Extracellular vesicles are nanosized vesicles released by cells. They mediate the functions of parent cells by delivering diverse active molecules from parent cells to selected target cells. Compared to ASCs, cell-free EVs can be better delivered to the fibrous tendon tissue and exhibit higher bioavailability in the hostile injury milieu due to their small size, stable membrane structure, and the ability to selectively target tendon cells and macrophages. Using a preclinical mouse tendon injury and repair model, we recently showed that iEVs produced by inflammation-primed ASCs can effectively improve tendon healing and functional recovery by inhibiting macrophage inflammatory response and increasing tendon cell population and collagen production at the injury site. Currently, we are collaborating with Drs. Farshid Guilak, Audrey McAlinden, and Ratna B. Ray (Saint Louis University), and investigating the active components and the mechanism of iEV action to develop component-defined and disease-selective EV drugs to treat tendon injuries effectively and safely.

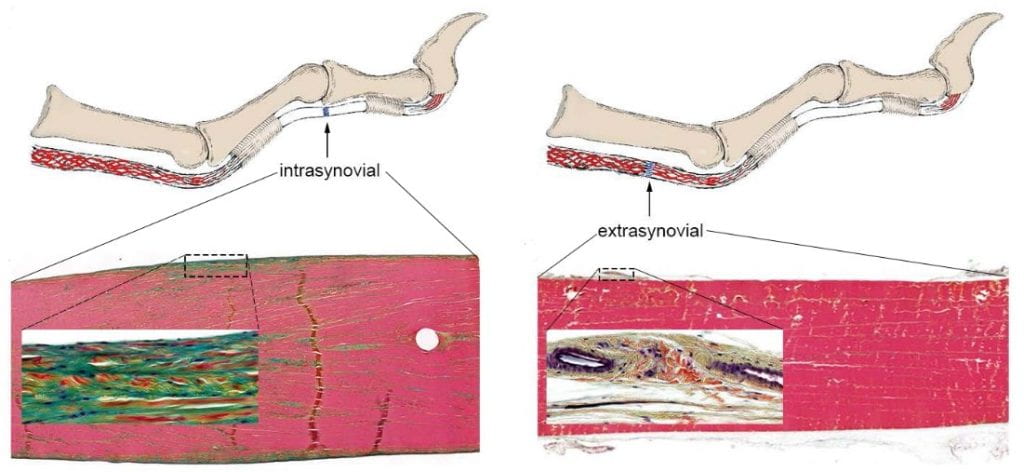

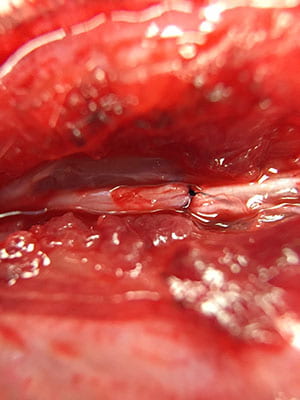

The Shen lab is also interested in the metabolic regulation of intrasynovial tendon healing. Intrasynovial flexor tendons fail to mount an effective healing response after injury, which contrasts with extrasynovial flexor tendons showing much higher healing capacity. In collaboration with Drs. Richard Gelberman, Stavros Thomopoulos (Columbia University), and Shelly Sakiyama-Elbert (Washington University), we recently discovered

iEVs target both residing tendon cells and infiltrating macrophages to promote tendon healing and functional recovery. Adapted from Shen & Lane. Stem Cells. 2023;41(6):617-627.

that flexor tendons from the intrasynovial and extrasynovial regions exhibit distinct metabolic profiles.

Hypovascular intrasynovial flexor tendons enriched in glycolytic enzymes preferentially generate ATP via glycolysis, while well-vascularized extrasynovial flexor tendons possess higher levels of enzymes involved in oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) and mostly use the pathway for energy production. Intrasynovial flexor tendons also express higher levels of pyruvate dehydrogenase kinase 1 (PDK1) that inhibits OXPHOS. Systemic inhibitions of PDK1 with dichloroacetate (DCA) shifted the metabolic preference of intrasynovial flexor tendons and led to increased tenogenic gene expression and neovascularization in the early phase of tendon healing. We are following up these findings investigating the impact of metabolic reprogramming on intrasynovial flexor tendon healing in vivo.

Along with these research projects, the Shen lab has established a set of innovative research tools, animal models and rigorous methodology. Being one of the first groups to study the therapeutic effect of stem cell EVs on tendon injuries, from EV isolation, sorting, and characterization to EV cargo identification, loading, and functional analyses, our lab has invented a set of methods in this emerging field. For drug development, we established several preclinical animal models for acute and chronic tendon injuries; we generated transgenic reporter mice for the longitudinal assessment of tendon injury response and healing process; we further developed several clinically relevant functional tests plus multilevel success criteria to evaluate treatment effect. We have also invented several drug delivery systems, including a collagen sheet for local delivery of diverse biologics to the injury site. Together, these innovations allow for rapid translation of basic findings into new biotherapeutics for tendon injuries.

Reference

1.

Gelberman, RH, Linderman, SW, Jayaram, R, Dikina, A, Sakiyama-Elbert, S, Alsberg, E, Thomopoulos, S. Shen, H. Combined Administration of ASCs and BMP-12 Promotes an M2 Macrophage Phenotype and Enhances Tendon Healing. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2017;475:2318-2331. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-017-5369-7

2.

Shen H, Yoneda S, Abu-Amer Y, Guilak F, Gelberman RH. Stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles attenuate the early inflammatory response after tendon injury and repair. J Orthop Res. 2020;38(1):117-127. J Orthop Res. 2020;38(1):5-6. https://doi.org/10.1002/jor.24406

Pentachrome-stained tendon sections at the intrasynovial (Left) and extrasynovial (Right) region of a flexor tendon show apparent differences in vascularity, cellularity, and extracellular matrices. Adapted from Shen, et al. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2021;103(9):e36.

3.

Shen, H, Lane, RA. Extracellular Vesicles from Primed Adipose-Derived Stem Cells Enhance Achilles Tendon Repair by Reducing Inflammation and Promoting Intrinsic Healing. Stem Cells. 2023;41(6):617-627.https://doi.org/10.1093/stmcls/sxad032

4.

Gelberman RH, Lane RA, Sakiyama-Elbert SE, Thomopoulos S, Shen H. Metabolic regulation of intrasynovial flexor tendon repair: The effects of dichloroacetate administration on early tendon healing in a canine mode. J Orthop Res. 2023:41(2):278-289. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/jor.25354

5.

Shen H, Yoneda S, Sakiyama-Elbert SE, Zhang Q, Thomopoulos S, Gelberman RH. Flexor Tendon Injury and Repair: The Influence of Synovial Environment on the Early Healing Response in a Canine Model. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2021;103(9):e36. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC8192118/pdf/nihms-1705373.pdf

Naomi Dirckx

Orthopaedic Surgery

- Email: dirckx@nospam.wustl.edu

Focus: The investigation of citrate and its plasma-membrane transporter, SLC13A5 in bone and cartilage.

Dr. Naomi Dirckx is Assistant Professor at the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery. Her lab’s research is focused on investigating the role of citrate, and it’s specific outside-in transporter called SLC13A5, in the process of bone mineralization and maintaining citrate balance in the body.

Osteoblasts, which are specialized cells derived from mesenchymal stem cells, play a crucial role in bone formation by synthesizing and depositing the organic matrix of bone. During the differentiation process, osteoblasts produce type I collagen and non-collagenous matrix proteins that form the organic fraction of bone. As osteoblasts further differentiate, they secrete calcium and phosphate ions, initiating the calcification process and forming hydroxyapatite nanocrystals that provide the structural integrity of the bone.

Citrate, a tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle intermediate, has been found to be a significant component of the apatite-collagen nanocomposite in bone. It is present at high concentrations in bone, constituting 1-5% of its weight. Studies have shown that the incorporation of citrate and its spatial orientation within the mineral structure are critical for maintaining favorable biomechanical properties of bone. Interestingly, research dating back to 1941 revealed that over 80% of the body’s total citrate is stored in the skeleton.

Apart from its production in the TCA cycle, citrate can also enter cells from the extracellular space through transmembrane dicarboxylate transporters. One specific transporter, SLC13A5, is a sodium-dependent citrate transporter that is highly expressed in the liver and brain. Defective citrate transport through SLC13A5 has been associated with protection against diet-induced insulin resistance and childhood epilepsy in these tissues. However, the exact role of SLC13A5 in osteoblasts is not well understood.

Her recent research has revealed that osteoblasts utilize a specialized metabolic pathway to regulate citrate uptake from the surrounding environment. This pathway involves the coordinated functioning of SLC13A5 and another protein called ZIP1, which is a zinc transporter encoded by the gene Slc39a1. When SLC13A5-mediated citrate transport is blocked, there is a drop in cytoplasmic citrate levels, relieving the inhibition on glycolysis and triggering the production of citrate from glucose within the TCA cycle. ZIP1, on the other hand, controls the subsequent secretion of citrate by inhibiting the mitochondrial aconitase enzyme, redirecting citrate away from the TCA cycle and allowing its secretion through the mitochondrial citrate transporter SLC25A1.

Mouse models where SLC13A5 was genetically disrupted, presented with elevated systemic citrate levels and an unexpected increase in mineral citrate levels in bones and teeth. These increased levels of mineral citrate impaired mineralization, resulting in reduced bone mass and strength as well as hypomineralized teeth without enamel. It is worth noting that these tooth abnormalities observed in mice with SLC13A5 loss-of-function mutations resemble the dental features seen in human patients with similar mutations. However, it remains unclear whether individuals with SLC13A5-related epilepsy also experience reduced bone volume and strength, as investigating this relationship in patients poses challenges due to the influence of their weak muscle tone (hypotonia) and lack of motor control (ataxia) on bone health.

The significance of her research lies in addressing osteoporosis, a debilitating condition characterized by low bone mass and increased fracture risk, which poses a growing burden on our aging population. Hip fractures, for instance, can have devastating consequences, with a 20% mortality rate within one year post-fracture, and the majority of survivors experiencing a loss of independence in daily activities. This condition is often termed a silent killer since bone loss often goes unnoticed until a fracture occurs. While advancements have been made in developing pharmaceutical treatments to improve bone mass in osteoporosis, these approaches have limitations and primarily focus on bone quantity, rather than the underlying mechanisms responsible for providing favorable mechanical properties to bone.

Understanding the mechanisms involved in bone mineral “citration” holds promise in improving bone quality in metabolic bone diseases. By investigating the role of citrate and the SLC13A5 transporter in osteoblasts, the aim to uncover new insights into the regulation of bone mineralization and potentially identify novel therapeutic targets for conditions like osteoporosis.

Through her interaction with TESS Research Foundation and interaction with families that have children with mutations in SLC13A5, she developed an interest in another non-skeletal manifestation associated with SLC13A5 mutations, namely epilepsy. Currently, the metabolic signature of neurons with deficient SLC13A5 transporters and the underlying cause of epilepsy remain unclear. A potential mechanism is that metabolite trafficking between astrocytes and neurons is affected by SLC13A5 deficiency. As previously observed in osteoblasts that lack this transporter, an increased amount of citrate was released to the expense of glutamine production. If astrocytes employ a similar mechanism, epilepsy could be evoked by 1) reduced glutamine trafficking to neurons leading to impaired neurotransmitter generation and 2) increased levels of citrate in the synaptic cleft modulating NMDA receptors.

Alex Reiter

Biomedical Engineering (Saint Louis University)

- Email: alex.j.reiter@nospam.slu.edu

Focus: Understanding the biomechanics of musculoskeletal soft tissue using methods ranging from preclinical models to wearable sensors in people.

Dr. Alex Reiter is an Assistant Professor in the Biomedical Engineering Department at Saint Louis University (SLU) and directs the Musculoskeletal Biomechanics Lab. Primarily focusing on tendon and muscle, his lab seeks to understand healthy tissue function and structure, assess changes that occur in injury or disease, and provide guidelines for improved treatment strategies. A common theme of his research career has been understanding how tissue loading following injury can improve outcomes. Dr. Reiter’s lab uses a diverse set of techniques from wearable sensors in humans to preclinical animal model testing.

Current work funded by the NIH aims to develop a noninvasive sensor to assess muscle-tendon loading in an animal model of volumetric muscle loss (VML). This project will simultaneously address two challenges. First, there are no techniques for noninvasively and directly measuring the in vivo force generating capacity of muscle in animals. Therefore, longitudinal tissue-level function testing is not possible, which limits the assessment of therapeutic strategies. Second, traditional physical therapy-based strategies for VML often reach a functional plateau well short of pre-injury capacity. Electrical stimulation will be investigated as a more targeted and tissue-specific method for improving outcomes.

With funding from the President’s Research Fund at SLU, his lab is characterizing tendon loading with a wearable sensor system in Achilles tendon rupture patients. They will determine if loading metrics hold predictive value for long-term outcomes. Following injury, early mobilization and progressive loading are initiated as part of the months-long current standard of care. While evidence suggests that loading early in the rehabilitation process yields favorable results for patients, functional deficits persist long-term in many, even when receiving gold-standard care. However, Achilles tendon loading has not been assessed as a predictor of long-term physical function and tendon structural outcomes. Furthermore, there are no validated techniques for directly monitoring tendon loading throughout rehabilitation. This project aims to address both of those gaps.

Hua Pan

Internal Medicine Division of Rheumatology

- Email: hpan@nospam.wustl.edu

Focus: Design and deployment of practical and safe solutions for unmet medical needs. I have extensive research experiences in developing molecular diagnosis and nano-based drug/gene delivery strategies for inflammatory diseases, including autoimmune arthritis, cardiovascular diseases, kidney diseases, and cancer.

The Pan lab is dedicated to developing innovative solutions aimed at enabling early diagnosis and treatment. By harnessing advanced delivery platforms, our lab leverages cutting-edge molecular and imaging biomarkers to identify high-risk populations and creates tailored interventions that address the unique needs of individuals within these groups. Please visit us at sites.wustl.edu/panlab

Join me as I share a story that starts with honeybees and reflects our commitment to developing novel solutions that leverage biocompatible materials for healthcare. Melittin is the main component, accounting for about 50% of the dry weight of bee venom. The amphipathic host-defense peptide melittin can rapidly insert into and remains stably bound to the lipid monolayer surrounding the perfluorocarbon (PFC) nanoparticles, facilitating anti-cancer applications by forming pores in the lipid bilayer of the cancer cell membrane, disrupting its integrity. Drawing from our knowledge of the structure-function relationship of melittin, we have engineered it to limit its lytic activity while retaining its ability to stably insert into lipidic carriers. Subsequently, a peptide linker has been created to enable a strategy that accommodates the swapping and/or combining of multiple cargos in generic base lipidic nanocarriers, allowing for flexible and personalized customization of these nanocarriers for specific pathological lesions and distinct disease stages, as shown in the left panel of the figure.

Originating from this linker peptide and leveraging our insights into peptide-nucleic acid interactions, we have established a nucleic acids delivery platform based on p5RHH, showing in the right panel of the figure. This novel biosensing peptide delivery platform provides protection for nucleic acids in circulation and effectively overcomes cellular barriers, including translocation through the hydrophobic core of the cell membrane and entrapment in endocytic compartments. This enables their successful cytoplasmic delivery. With its favorable safety profile, this delivery system has been successfully used by numerous collaborating academic groups for systemic delivery of nucleic acids, small or large, beyond the liver, addressing a wide range of pathologies, including atherosclerosis, abdominal aortic aneurysm, adult T-cell leukemia/lymphoma, tumor angiogenesis and immunity, lung cancer, pancreas cancer, ovarian/uterine cancers, necrotizing enterocolitis, metabolic syndrome, rheumatoid arthritis, and osteoarthritis.

We are committed to developing new healthcare solutions through advanced technologies that empower our collaborators to utilize these innovations in their own laboratories.

2023

Rebekah Lawrence

Physical Therapy

- Email: r.lawrence@nospam.wustl.edu

Focus: Understanding the modifiable biomechanical factors underlying shoulder pain and pathology leading to the development of evidence-based rehabilitation strategies.

Rebekah Lawrence, PT, PhD is an Assistant Professor in Physical Therapy and Orthopaedic Surgery at Washington University and leads the Shoulder Biomechanics and Rehabilitation Laboratory. Broadly speaking, her research program is focused on investigating the factors associated with shoulder pathology, symptom manifestation, and functional decline. This work is guided by her clinical experience as a physical therapist, leveraged by her research training in biomechanics, modeling, and rehabilitation science, and complemented by the expertise of a multi-disciplinary research team.

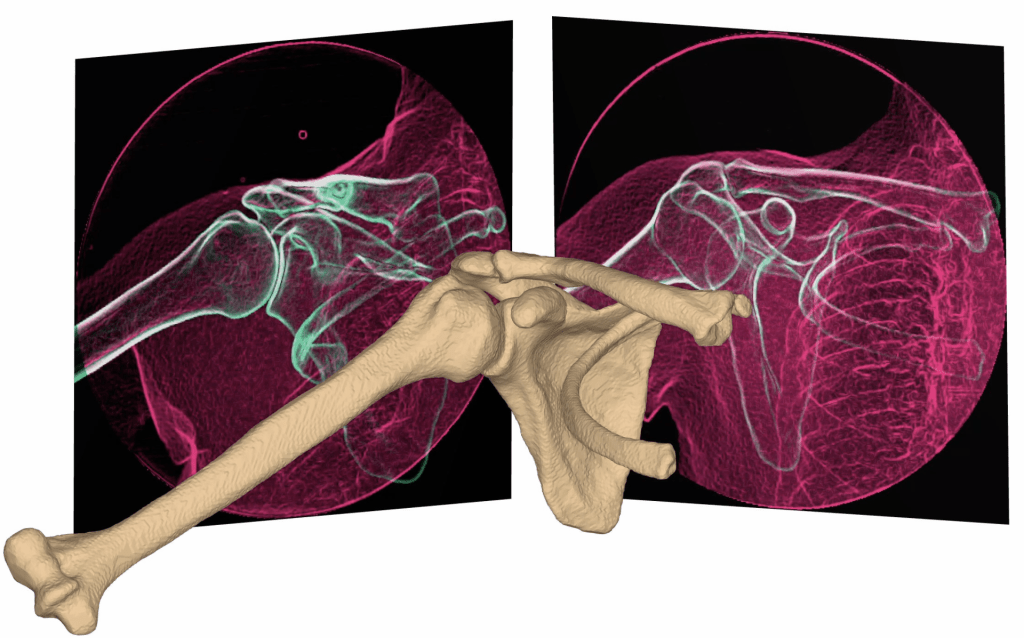

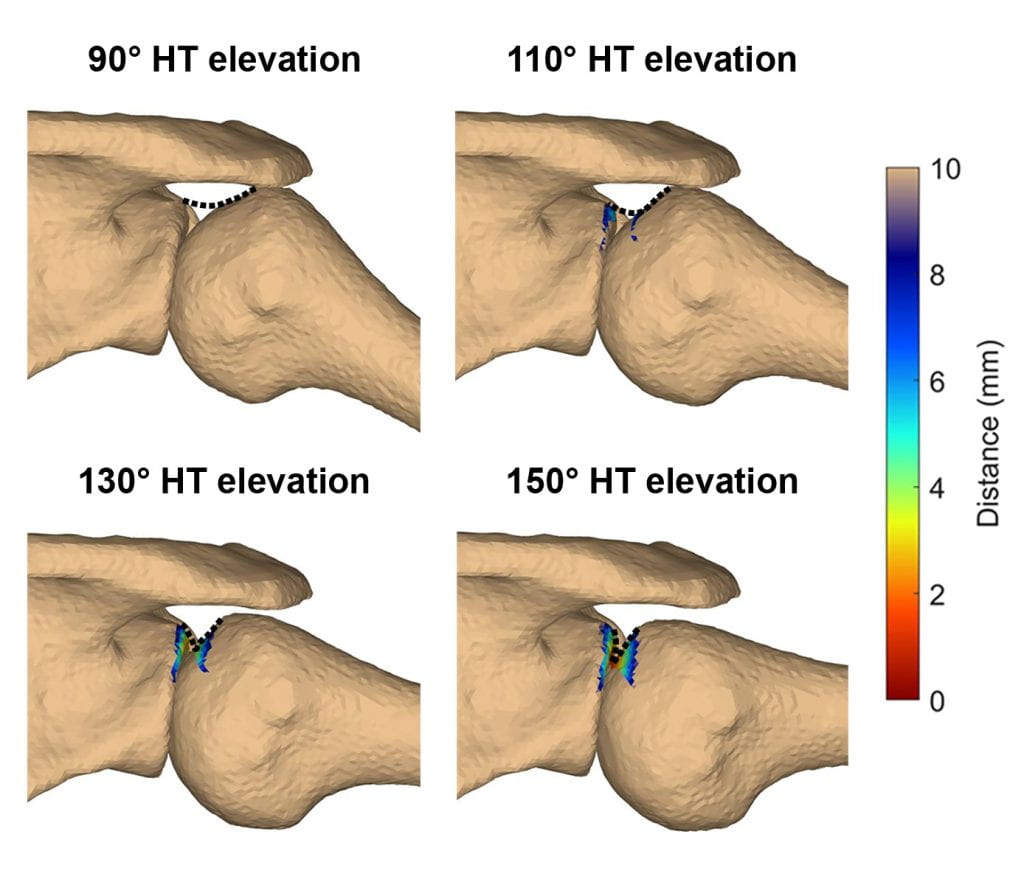

Current work funded by an NIH K99/R00 is investigating the multifactorial etiology of supraspinatus tendon tears. To date, this study has demonstrated that occupational exposure and variations in shoulder morphology associated with higher rotator cuff tendon loading are strong predictors of a supraspinatus tendon tear. These findings suggest that chronic tensile overload may play an important role in the development of supraspinatus tears. The next phase of the study will validate these results in an independent cohort, and then seeks to identify characteristics that differentiates individuals with a tendon tear who have maintained their shoulder function vs. those who experience pain and functional decline. The goal of this work is to identify targeted prevention and treatment strategies for individuals with shoulder pain.

A second line of work seeks to understand the patient, tissue, and rehabilitation factors that affect repair integrity and functional outcomes after rotator cuff repair. This work is motivated by the clinical problem that shoulder dysfunction often persists even after surgical repair of a torn rotator cuff. We believe this disconnect may be due to both repair tissue elongation and chronic muscle changes, which alter the glenohumeral joint’s mechanical environment. Future work will investigate these to develop patient-specific rehabilitation guidelines for individuals after rotator cuff repair.

Nathaniel Huebsch

Biomedical Engineering

- Email: nhuebsch@nospam.wustl.edu

Focus: Engineered disease models, hydrogel biomaterials for regenerative medicine approaches to bone and intervertebral disc.

Nate Huebsch is an Assistant Professor of Biomedical Engineering at Washington University where he leads a laboratory focused on basic and translational mechanobiology. The lab’s work is on understanding how mechanical cues modify cells’ respond to soluble cues like growth factors, and to underlying genetic variation. Broadly, the lab’s work is divided into two areas. The first area is focused on meeting the promise of personalized medicine by creating tissue engineered in vitro models of heart disease that incorporate both genetic and mechanical factors. The second area is in understanding mechanisms for crosstalk between mechanical and chemical signaling and leveraging this understanding toward regenerative medicine.

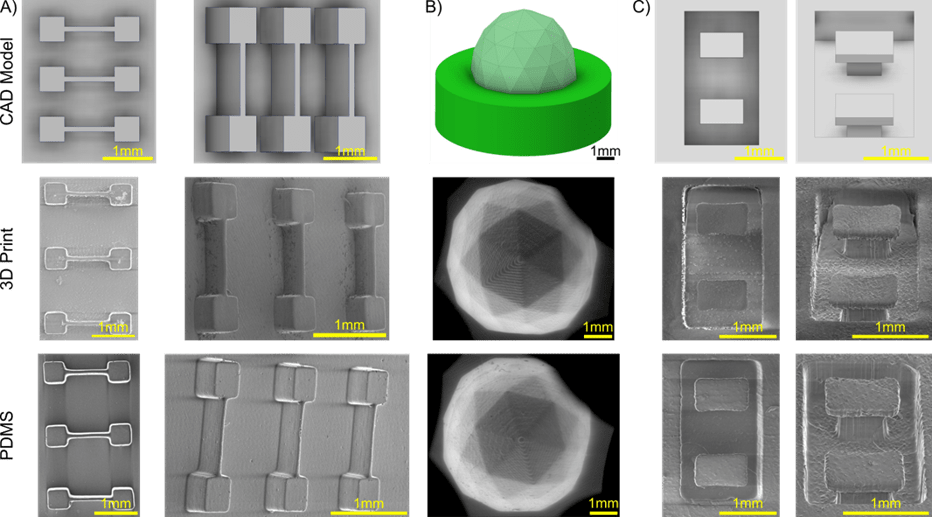

Work on cardiac biology centers around hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, the most common cause of arrhythmias in young people. While this disease is linked to mutations in the contractile sarcomere apparatus that allows heart muscle to contract, penetrance is variable, to the extent that even within the same family, mutation-positive individuals can have dramatically different phenotypes. To study how mechanical forces on heart muscle might act as a trigger to progression of this disease, Huebsch’s team engineers miniaturized heart tissue from human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSC) and forces the muscles to work against elastomer substrates. Within these engineered tissues, iPSC-derived heart muscles with disease-linked mutations in Myosin Binding Protein C (MYBPC3) exhibit several hallmarks of hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, including abnormal contractility, cardiomyocyte enlargement and abnormal electromechanical coupling. Recent studies in which the elasticity of these substrates is dynamically increased in the revealed that engineered heart muscle rapidly adapts to mechanical changes. Parallel studies have shown that a threshold level of prestress on cardiomyocytes within engineered tissues is required for functional development of sodium channels, which are critical for normal electrical conduction. Future work will focus on identifying the molecular machinery that cardiomyocytes use to adapt to mechanical challenges, and how MYBPC3 mutations affect this adaptation. Studies on engineered heart muscle in the Huebsch lab leverage several bioengineering advances made by the group, most recently in methods to rapidly and easily create molds to control tissue shape – these methods can be extended to skeletal muscle in the future.

Work to understand crosstalk between mechanical and chemical signaling in the Huebsch lab is based on the longstanding observation that integrin signaling is required for many chemically-induced cell fate changes, including Bone Morphogenetic Protein signaling. Integrins are critical for cells’ ability to sense their mechanical environment, and typically act in concert with growth factor receptors. Using injectable alginate hydrogels as a synthetic extracellular matrix mimic, the group has found that short, easily manufactured peptides derived from Bone Morphogenetic Protein 2 and Insulin Like Growth Factor 1 can mimic the activity of full length growth factors in terms of their ability to elicit differentiation and secretion of immunomodulatory factors from Mesenchymal Stromal Cells (MSC). Unlike the full length growth factors, however, these peptides can easily be grafted to hydrogels to prevent off-target delivery. Interestingly, however, these peptides do not induce MSC fate changes in the absence of integrin-binding peptides like cyclic-RGD. Future studies are aimed at leveraging the capabilities of these growth factor mimicking hydrogels to improve MSC therapeutic potency for regenerative applications including repair of degenerative disc disease.

Rita Brookheart, PhD

Internal Medicine – Pediatrics

- Email: rbrookheart@nospam.wustl.edu

Focus: skeletal muscle function and metabolic flexibility in response to stress (e.g., exercise, prolong fasting, and injury) and how these responses are impacted by metabolic disruptions — particularly obesity and diabetes.

Rita T. Brookheart is an Assistant Professor in the Division of Nutritional Science and Obesity Medicine at Washington University School of Medicine. Rita received her PhD from Washington University in St. Louis as an NRSA Predoctoral Fellow (F31) and completed an NRSA Postdoctoral Research Fellowship (F32) at the Johns Hopkins School of Medicine before returning to Washington University. As a faculty member at Washington University, Rita has been awarded several grants in support of her research including an NIH Building Interdisciplinary Research Careers in Women’s Health (BIRCWH) K12 Award, an NIH-NHLBI K01 Career Development Award, and Washington University NORC and MRC Pilot and Feasibility Awards.

In 2021, Rita started her independent research lab (https://brookheartlab.wustl.edu/) primarily focused on understanding the intersection of metabolism and stress responses in human health and disease. Her lab seeks to identify the mechanisms by which metabolic disruptions evident in obesity and diabetes impact muscle function and strength through the use of basic and translational approaches.

Her lab recently identified an underappreciated function for the protease S1P in muscle biology (Mousa, et al.). S1P is a key activator of several transcription factors essential for lipid biosynthesis and proteostasis. S1P has classically been studied in the liver and bone; however, its function in muscle has been less clear. After her group’s clinical study of a patient with an S1P mutation who exhibited myoedema, exercise intolerance, and myalgias with hyperCKemia (Schweitzer, et al.), her lab hypothesized that S1P may control muscle metabolism and exercise endurance. Upon generating a skeletal muscle-specific S1P knockout mouse line, Rita’s lab discovered that S1P null mice had greater muscle mass and increased mitochondrial respiration. Interestingly, this increase in muscle mass was maintained as the knockout mice aged. Her lab was able to show that S1P controlled muscle metabolism by promoting expression of the TGF-beta target gene MSS51. These data implicated S1P as a regulator of organ mass and mitochondrial function.

Current work in the lab is focused on elucidating the mechanisms by which S1P controls organ size and metabolism and whether such S1P-driven phenomena occur in other organ systems and can be harnessed for treating human disease.

Koyal Garg

Saint Louis University – Biomedical Engineering

- Email: koyal.garg@nospam.slu.edu

Focus: develop novel biomaterial and stem cell based regenerative therapies and electrical stimulation based rehabilitative strategies to promote the recovery of skeletal muscle following trauma.

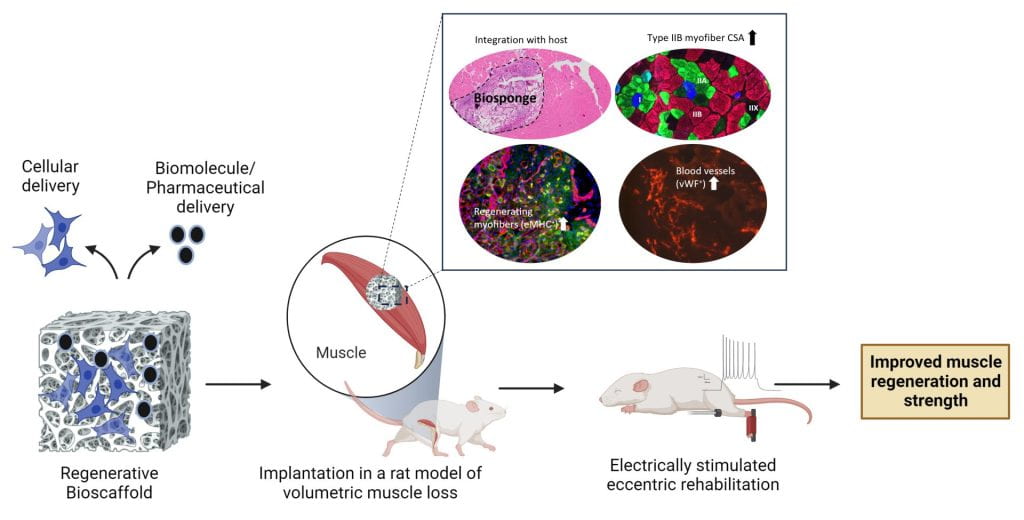

Dr. Koyal Garg is an Associate Professor in the Biomedical Engineering department and holds a secondary appointment in the Department of Pharmacology and Physiology at Saint Louis University. Her research focuses on developing regenerative and rehabilitative strategies for traumatic muscle injuries such as volumetric muscle loss (VML). To promote functional muscle repair following VML, her lab is developing bioinspired extracellular matrix (ECM) based biomaterials that can serve as regenerative templates or as delivery vehicles for stem cells, extracellular vesicles, biomolecules, and pharmaceuticals. An example of such a material is the biosponge, a porous scaffold composed of chemically crosslinked gelatin, collagen, and laminin-111. Implantation of biosponges in VML rodent models resulted in increased muscle mass, myofiber regeneration, vascularity, type IIB myofiber cross-sectional area, and function. To rehabilitate VML injured muscle in rodents, her lab has developed an eccentric contraction-based strength training protocol using neuromuscular electrical stimulation. Implementing this rehabilitation protocol improved muscle mass, myofiber cross-sectional area, and muscle function following VML. Recent work in the lab has shown that these regenerative and rehabilitative approaches can be successfully combined to improve muscle structure and function while mitigating muscle fibrosis following VML injuries.

Dr. Garg’s research has been funded by the Department of Defense (DOD), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Alliance for Regenerative Rehabilitation Research and Training (AR3T), and the BioSTL’s Center for Defense Medicine. Her students have launched a startup company, GenAssist, committed to commercializing and clinically translating biosponge technology for VML repair. Dr. Garg has been recognized as an outstanding graduate faculty by the School of Engineering at SLU both in 2019 and 2022. Additionally, she was honored as a WISER (Woman in Science, Entrepreneurship, & Research) woman by the Missouri Cures Education Foundation in Feb 2022, showcasing her commitment to STEM leadership, innovation, and advancement of women in these fields.

2022

Jennifer Zellers

Program in Physical Therapy

- Email: jzellers@nospam.wustl.edu

Focus: Optimize treatment for tendon dysfunction by personalizing dosing of tendon loading and aligning adjunctive treatments to promote the mechanical and biochemical environment needed for tendon repair and remodeling.

Jennifer Zellers, PT, DPT, PhD, is Assistant Professor in Physical Therapy and Orthopaedic Surgery at Washington University and is Director of the Tendon Rehabilitation Laboratory (Tendon Rehab Lab). She is a translational, tendon researcher with a clinical background as a physical therapist. Her research program leverages ex vivo assessment of human tissues along with in vivo assessment of human tendon and patient functional performance outcomes (via diagnostic imaging and performance testing) to bridge basic and clinical science approaches to understanding tendon injury and recovery.

Dr. Zellers’s past work identified indicators of tendon recovery early after Achilles tendon rupture using non-invasive ultrasound imaging and elastography. These studies demonstrated that tendon characteristics including cross sectional area and mechanical properties normalize over time post-rupture, but they do not fully recover symmetry to the uninjured side. Asymmetries in tendon morphology and mechanical properties also relate to patient performance with walking, heel-rise, and jumping, pointing to the potential of using tendon characteristics on ultrasound as predictors of tendon healing trajectory during early recovery when patient performance on higher level tasks is unable to be assessed.

Helen McNeill

Developmental Biology

- Email: mcneillh@nospam.wustl.edu

Focus: Regulation of growth and patterning. Our recent preliminary data in Drosophila has indicated that a poorly understood nuclear envelope protein, Nemp, is required for fertility and muscle stem cells. We are interested in determining if this is true for mammals. We have generated Nemp1 mutant mouse, and our recent preliminary data suggest a role in the muscle and skeleton. In addition, we study Fat4, a large cadherin. Mutations in Fat4 are associated with Van maldergem syndrome, which is characterized by a range of defects, including skeletal defects. We have generated targeted mutations in Fat4 in mice with CRISPR, and want to determine if there are defects in muscle and skeleton.

Helen McNeill, PhD, is the Larry J Shapiro and Carol-Ann Uetake-Shapiro Professor in the Department of Developmental Biology at Washington University School of Medicine and is co-director of the Graduate Program of Developmental, Regenerative and Stem Cell Biology. Helen joined WUSM in 2018, moving her lab from Toronto, Canada, where she was a Professor at the University of Toronto, a scientist at the Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute and Director of the Collaborative Program in Developmental Biology. She first established her independent research group in London, England, at Cancer Research UK. Her research program explores basic mechanisms of cell and developmental biology, using Drosophila and mouse models. Her research has focused on two problems; 1) How do Fat cadherins and the Hippo pathway regulate tissue growth and patterning? and 2) How does a novel family of nuclear envelope proteins (NEMP) support the nuclear envelope, prevent laminopathies and support fertility? Remarkably, in the past two years, recent research in the McNeill lab has uncovered roles for both Fat cadherins and NEMP1 in musculoskeletal biology.

Her lab previously identified Nemp family proteins as critical in supporting fertility in Drosophila, C. elegans, zebrafish and mice (Tsatskis et al., 2020 Science Advances). In that study they showed that NEMP1 mechanically supports the nuclear envelope and functions with LEM domain proteins such as the laminopathy associated protein Emerin. More recently, they discovered that NEMP proteins play essential roles in muscle development and function in Drosophila and are now investigating NEMP1 function in mouse muscle in both development and regeneration, working with the Johnson lab and the Musculoskeletal Research Center’s Structure and Strength Core.

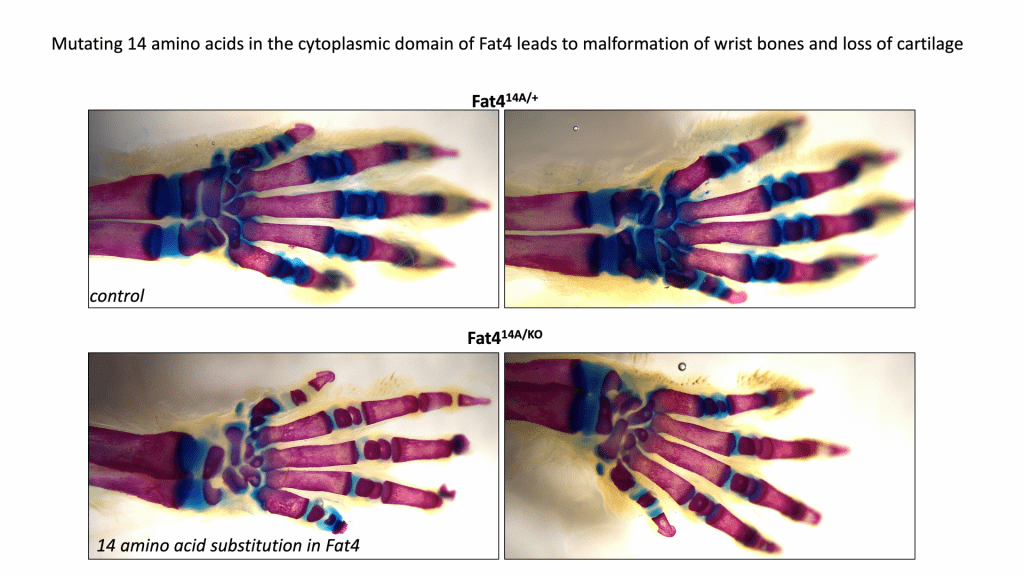

Drosophila Fat (Ft) cadherins are enormous cell adhesion molecules that regulate tissue organization, metabolism and proliferation via the Hippo pathway. Mutations in FAT4 (the human homolog of Ft) lead to Van Maldergem’s syndrome, associated with neural defects, craniofacial defects and short stature. The McNeill lab (with the WUSM transgenic core) recently generated mice mutant in conserved regions of the cytoplasmic domain of Fat4 . Remarkably, mutations of just a few residues of Fat4 lead to defective cartilage and joint development and dramatic reduction of the growth plate. Spencer Willet in the lab is currently working with several MRC cores, and collaborating with labs at WUSM (Ornitz, McAlinden), to understand how mutation of Fat4 leads to loss of collagen and defects in bone growth and joint formation.

Charlotte Phillips

Biochemistry and Child Health | Univ. of Missouri

Focus: The molecular/biochemical pathogenesis of osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) in mineralized and non-mineralized tissues, with a recent focus to develop alternative pharmacologic and therapeutic strategies to enhance muscle and bone quality and biomechanical integrity.

My laboratory’s research focus is to investigate the pathogenesis of osteogenesis imperfecta (OI) in both skeletal and non-skeletal tissues and to evaluate therapeutic agents and strategies to enhance muscle and bone using OI mouse models. OI is a heritable connective tissue disorder due primarily to mutations in type I collagen genes resulting in decreased bone mineral density (BMD), frequent fractures, and muscle weakness. Disease severity ranges from mild with few fractures to perinatal lethal with marked bone deformity and fragility. There is no cure. The primary therapeutic strategies of anti-resorptive agents and surgical bracing have limited success and significant concerns of adverse effects. The genetic and clinical heterogeneity (> 1500 mutations) of has led our research team to focus on maximizing muscle and skeletal strength through identifying and exploiting mechanisms of muscle-bone crosstalk, whether biochemical, through mechanotransduction, and/or developmental programming, that can maximize peak bone mass.

Myostatin is a negative regulator of muscle fiber growth and differentiation through the activin receptor type IIB (ActRIIB). Dr. Youngjae Jeong (formerly a graduate student – currently a Postdoctoral Fellow, Baylor College of Medicine) demonstrated that postnatal treatment (8-16 weeks of age) with a myostatin receptor decoy, sActRIIB-mFc, increased muscle and bone mass and strength in wildtype (Wt) and two OI mouse models (oim/oim and +/G610C)(1,2). However, in clinical studies, sActRIIB-mFc was associated with adverse side-effects, attributed to off target binding. Thus, we are pursuing new agents with increased specificity, including anti-myostatin specific monoclonal antibodies. Additional investigations by a previous graduate student, Dr. Catherine Omosule (currently a Chief Clinical Chemistry Fellow, Department of Pathology and Immunology, Division of Laboratory and Genomic Medicine

Washington University) demonstrated treatment with anti-myostatin monoclonal antibodies, regardless of genotype or sex, increased skeletal muscle weights and increased bone trabecular microarchitecture in Wt and to a lesser extent in the OI mice(3). The postnatal antibody also elicited femoral biomechanical improvements (determined by 3-pt bend analyses; maximum load, and work to failure) in male Wt mice and reverted bone volume (BV) in male +/G610C mice to control Wt levels. However, in separate studies Dr. Omosule and Dr. Arin Oesterich (former graduate student, currently a Research Instructor, Washington University School of Medicine Department of Orthopedic Surgery) demonstrated more significant improvements were achieved when OI mice were also genetically deficient for myostatin, suggesting prenatal and/or early life myostatin inhibition is critical for maximum efficacy(3-5). Furthermore, Dr. Oestreich as a graduate student demonstrated by three independent approaches, that reduced maternal myostatin during pregnancy improved bone geometry and biomechanical integrity in offspring: 1) Wildtype (Wt) offspring born to dams with reduced myostatin (+/mstn) had stronger bones than Wt offspring born to Wt dams; 2) Mice with osteogenesis imperfecta (+/oim) had stronger bones when born to +/mstn dams than when born to +/oim dams; and 3) +/oim blastocysts transferred to +/mstn recipient dams had stronger bones as adults than those transferred to +/oim dams(4). Importantly, the last approach demonstrated through embryo transfer experiments that the maternal +/mstn effect on offspring bone is conferred by the uteroplacental environment during pregnancy. However, in contrast to genetic myostatin reduction, which is present from conception, postnatal myostatin inhibition appears unable to improve bone biomechanical function in the oim/oim or +/G610C mice to that of +/mstn +/oim(5) and +/mstn +/G610C(3), further emphasizing the importance of the prenatal therapeutic window.

Our current focus is to test the efficacy of pharmacological inhibition of maternal and fetal myostatin during pregnancy, lactation, and early adulthood in two molecularly distinct OI mouse models.

- Jeong Y, Daghlas SA, Kahveci AS, et al. Soluble activin receptor type IIB decoy receptor differentially impacts murine osteogenesis imperfecta muscle function. Muscle Nerve. 2018;57(2):294-304.

- Jeong Y, Daghlas SA, Xie Y, et al. Skeletal Response to Soluble Activin Receptor Type IIB in Mouse Models of Osteogenesis Imperfecta. J Bone Miner Res. 2018;33(10):1760-72.

- Omosule CL, Gremminger VL, Aguillard AM, et al. Impact of Genetic and Pharmacologic Inhibition of Myostatin in a Murine Model of Osteogenesis Imperfecta. J Bone Miner Res. 2021;36(4):739-56.

- Oestreich AK, Kamp WM, McCray MG, et al. Decreasing maternal myostatin programs adult offspring bone strength in a mouse model of osteogenesis imperfecta. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(47):13522-7.

- Oestreich AK, Carleton SM, Yao X, et al. Myostatin deficiency partially rescues the bone phenotype of osteogenesis imperfecta model mice. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27(1):161-70.

Harrison Gabel

Neuroscience

- Email: gabelh@nospam.wustl.edu

Focus: Dissecting the epigenetic processes underlying Overgrowth and intellectual disability disorders (OGIDs). Our lab uses integrated analysis of epigenomic and transcriptomic alterations across multiple neurodevelopmental disease models to understand the genetic basis of these disorders.

Harrison Gabel, PhD, is an associate professor in the Department of Neuroscience at Washington University School of Medicine. He started his laboratory at WUSM in 2015, after completing his doctoral and postdoctoral training at Harvard Medical School. Dr. Gabel’s research group is focused on understanding molecular mechanisms of gene regulation that contribute to development, with a particular interest in how transcriptional regulation contributes to function and plasticity in the mammalian brain. The lab combines genetic, genomic, and biochemical approaches in mouse and human models to identify and dissect important gene-regulatory pathways in neurons. A broad goal of this work is to understand how disruption of transcriptional regulation can lead to autism and related neurodevelopmental disorders. His group has published studies on molecular mechanisms of Rett syndrome, CHARGE syndrome, and additional autism spectrum disorders.

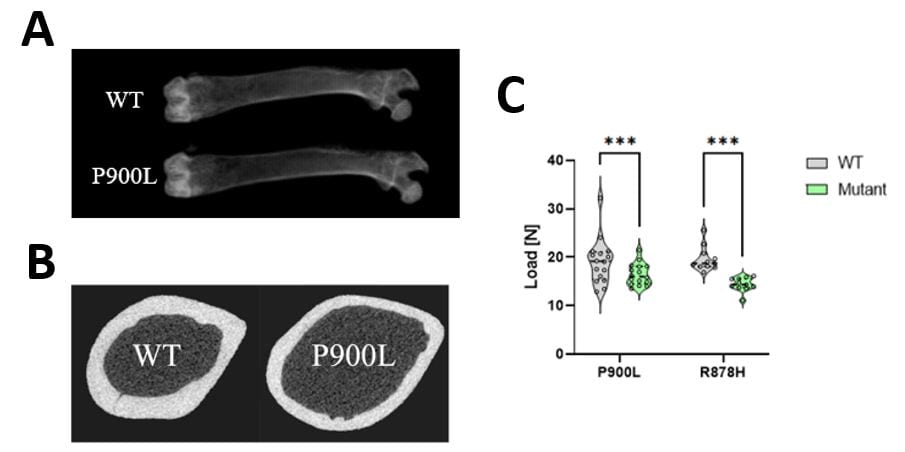

Recently, Dr. Gabel’s research group has developed multiple mouse models of the overgrowth and intellectual disability disorder, Tatton-Brown Rahman Syndrome (TBRS). TBRS is one of several overgrowth and intellectual disability syndromes that have not been extensively studied. While his lab started TBRS studies focused exclusively on disruption of nervous system function in these models, engaging with the MRC faculty and research cores has allowed his group to investigate overgrowth and orthopaedic phenotypes associated with the disorder. In collaboration with Dr. Audrey McAlinden in the Department of Orthopaedics, Dr. Gabel’s group has employed dual X-ray and µCT imaging to characterize long bone overgrowth which faithfully recapitulates human overgrowth in TBRS. This work has revealed that TBRS mouse models have increased femur length, thinner cortical bone, and weaker bones in the 3-point bending test (Figure 1). Ongoing work using histological analysis and dynamic histomorphometry is dissecting the cellular drivers of overgrowth during growth and development and its impact on skeletal function in these mice. These studies are beginning to characterize musculoskeletal pathology in TBRS and related overgrowth and intellectual disability disorders.

Dr. Gabel notes, “The wonderful collaborative atmosphere at WashU and the MRC, together with the access to great resources at the MRC, have been instrumental in our work branching out into skeletal phenotypes of TBRS. Working with Dr. McAlinden and engaging with the MRC cores has allowed us to begin to address this understudied but critical aspect of overgrowth and intellectual disability disorders.”

Learn more about the Gabel lab’s research at https://sites.wustl.edu/hgabellab/

Rajeev Aurora

Saint Louis University – Molecular Microbiology & Immunology

Focus: the mechanisms that lead to chronic inflammation.

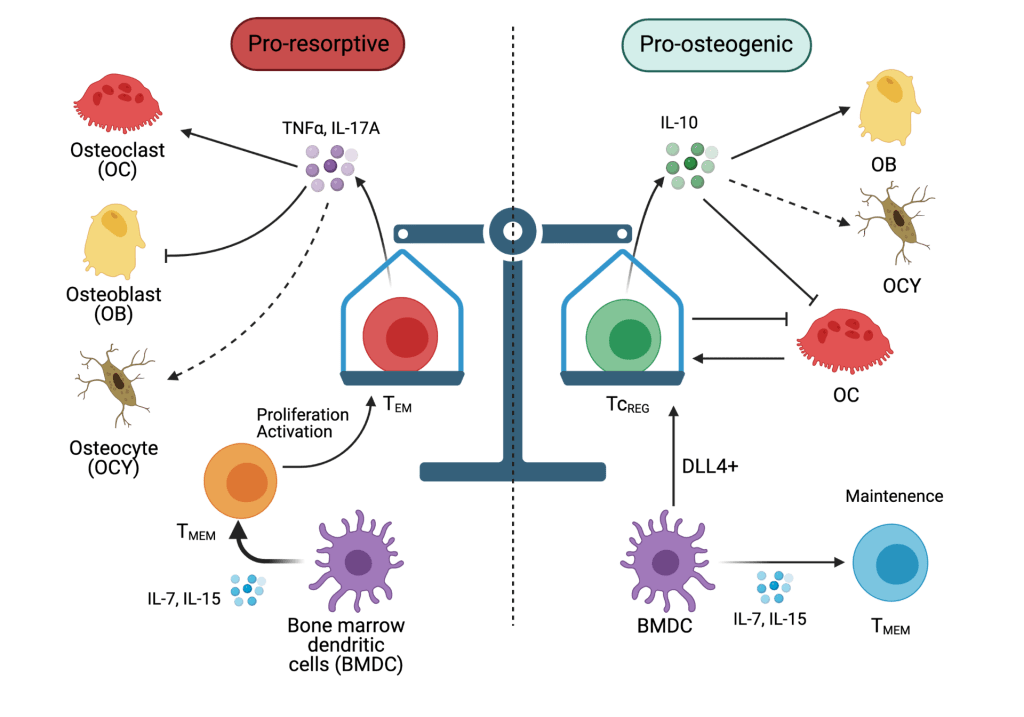

Dr. Aurora is an Associate Professor in Molecular Microbiology and Immunology at Saint Louis University School of Medicine. Dr. Aurora’s laboratory identified a novel mechanism by which estrogen (E2) loss, triggers the activation of tissue resident memory T-cells (TRM). E2 induces FasL in dendritic cells (DC) that secrete IL-7 and IL-15 (see Figure). Both these cytokines are key regulators of TRM homeostasis. In the absence of E2 in ovariectomized mice, a mouse model for postmenopause, the DC become long-lived leading to increased levels of IL-7 and IL-15. In High levels of IL-7 and IL-15, causes the antigen-independent proliferation and to secretion of TNFα, IL-17A or both, in a subset of the TRM. These two proinflammatory cytokines increase the sensitivity of osteoclast precursors towards RANKL, resulting in increased osteoclasts. They also increase activity of mature osteoclasts resulting in rapid bone loss observed in the acute phase of postmenopausal osteoporosis. TNFα and IL-17A also targets osteoblasts and osteocytes to promote dysfunction, and consequently resulting in poor bone quality.

The focus of the Aurora lab is Osteoimmunology. Aging and certain types of chronic inflammation due to autoimmune disease, persistent infections and hormonal imbalance lead to bone loss and effete bone that fractures with minimal trauma. Our focus is to identify mechanisms and, additionally, to develop immune therapy that restores bone with good biomechanical properties.

Our laboratory has also demonstrated that in addition to the bone resorbing activity of mature osteoclasts, these cells also can take up, process and present exogenous antigens. Antigen presentation by osteoclasts to CD8 T-cells leads to induction of FoxP3, CD25, interleukin (IL)-2, CTLA4, interferon (IFN)-γ and IL-10 by the CD8 T-cells. We refer to the osteoclast induced FoxP3+ T-cells as TcREG. We found that treating with low dose RANKL, but not the same dose of RANKL administered continuously (by a pump) induces TcREG. Interestingly, each of the cytokines produced by TcREG has a unique function in the bone: IFN-γ leads to the degradation of TRAF6 in osteoclast precursors rendering them insensitive to RANKL; IL-10 targets osteoblasts and osteocytes to promote new bone formation, and CTLA-4 leads to reducing TNFα and IL-17A expression by TRM. Thus, induction of TcREG by pulsed RANKL treatment limits bone loss, and proinflammatory cytokines as well as being bone anabolic. We observe bone with restored good biomechanical properties only when we target osteoclasts, osteolineage and TRM. Targeting each function alone has only a partial effect on improving biomechanical properties: increasing bone mass (via IFN-γ only), increasing osteolineage activity (IL-10 only) and reducing inflammation (via CTLA-4 – costimulatory molecule interactions). These results are consistent with use of drugs like bisphosphonates or teriparatide alone.

2021

Francesca Fontana

Internal medicine

Focus: biology and nanotherapy of bone cancer, multiple myeloma, molecular oncology, bone biology, cell adhesion molecules in bone and cancer. The overarching goal of my research is gaining insight into the biology of cancer and bone cells in order to develop and validate novel targeted therapeutic and diagnostic strategies.

Dr. Fontana graduated in Medicine from Vita-Salute San Raffaele University (Milano, Italy), where she started working in clinical research on skeletal cancer. Transitioning to the bench, in 2012 she completed her PhD in molecular medicine, working on metabolism of multiple myeloma (MM). The following year, a fellowship from Fondazione Veronesi allowed to her to move to Washington University Schoool of medicine, where in 2014 she formally joined the laboratories of Dr. Katherine Weilbaecher and Dr. Roberto Civitelli. Her postdoctoral work revolved around the use of in vivo models to study the functions of cell adhesion molecules in bone physiology and the tumor microenvironment, or to translate characterization of myeloma metabolism of acetic acid into PET imaging.

In fall 2018, Dr. Fontana joined the “C-TRAIN” (Washington University Consortium for Translational Research in Advanced Imaging and Nanomedicine), directed by Dr. Gregory Lanza, to complement the team’s work on development of nanotherapeutics by offering a cell and cancer biology perspective. Two years later, she was appointed research instructor in medicine within the same group.

CTRAIN is an 18,000 sq. ft diversified but integrated research complex, which has been home to varying numbers of PIs since 2006. CTRAIN laboratories include formulation chemistry, nuclear magnetic resonance, molecular and cellular biology, histology, radiochemistry, small animal handling and imaging, among others. Leveraging on national and international collaborations in academia, industry, and clinic, CTRAIN aims at developing technological advances into applicable diagnostic and therapeutic tools.

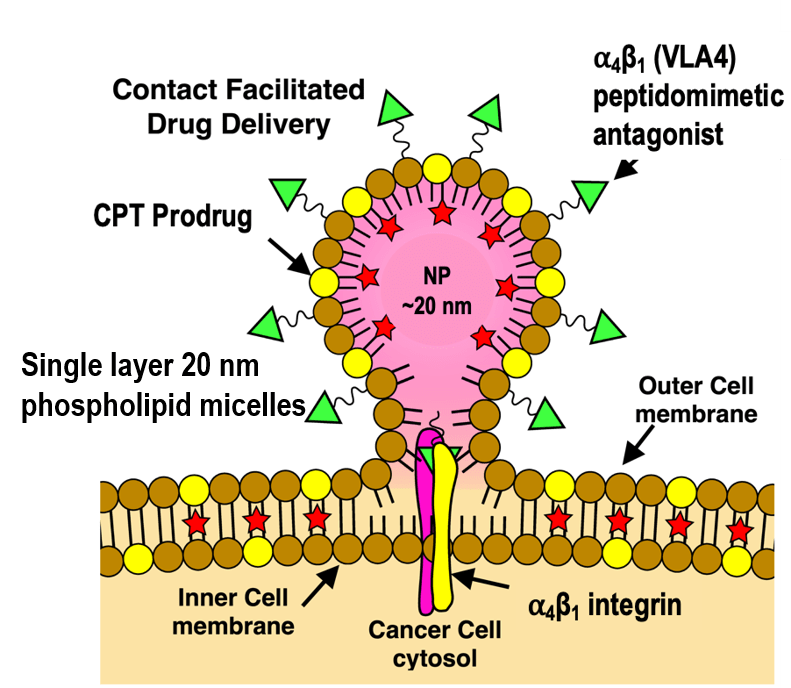

Nanotherapeutics are generally characterized by a targeting group, a carrier, and a payload. The pro-drug nanomicelle system patented by the Lanza lab conjugates the drug payload and the homing ligand to phospholipids that integrate into the nanomicelle’s single-layer lipid shell, creating shelf-stable organic particles capable of packing multiple molecules of payload while remaining 60% smaller than a single IgM.

In a process named contact-facilitated drug delivery (CFDD), nanoparticles attach to their target by high affinity homing ligands, allowing the phospholipid layer to fuse with the cell membrane. Enzymatic hydrolysis then releases the active drug into the cytoplasm. A recent study describes the use of such nanoparticles designed to target drug-resistant myeloma cells (doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-2839)

Multiple myeloma is a relapsing-recurring neoplasia of bone marrow plasma cells, which causes systemic organ damage and severe osteolytic bone lesions. Novel treatments have significantly prolonged survival, but none of them can completely eradicate the disease: at each relapse myeloma cells accumulate resistance against drugs, while patients accumulate organ damage from off-target effects of treatments or the cancer itself. A critical need is therefore to develop treatments with extremely low toxicity but capable of overcoming drug resistance.

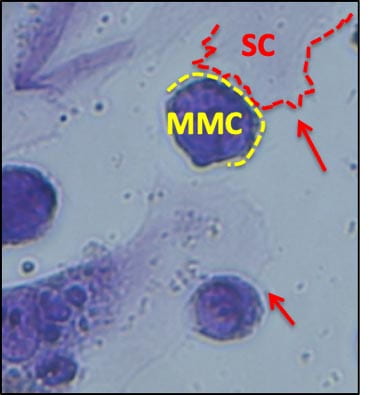

One of the main mechanisms that allow myeloma cells (MMC) to survive chemotherapy is the protective effect of the bone microenvironment. Integrin VLA4 mediates adhesion of MMC to the bone matrix and stromal cells, conferring resistance to the toxic effects of a wide variety of treatments. Indeed, myeloma cells surviving chemotherapy overexpress VLA4, and in vitro can be found nearly surrounded by stromal cells. Based on this observation, we hypothesized that nanotherapeutics targeting of VLA4 in conjunction with conventional chemotherapy would create a “catch-22” situation for MMC: low VLA4 expression would make them sensitive to conventional drugs, but overexpressing VLA4 to resist chemotherapy would make them vulnerable to targeted nanoparticles.

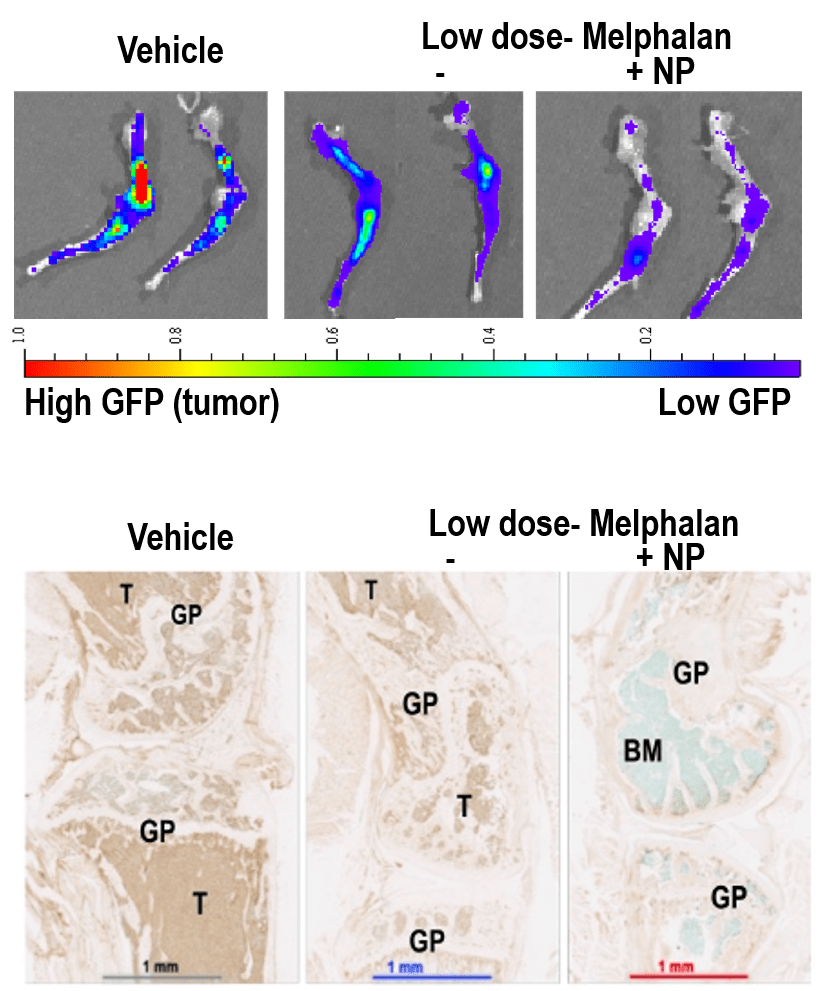

VLA4 overexpressing myelomas showed higher expression of topoisomerase 1, target of camptothecin. Matching the payload to the homing ligand, a semisynthetic camptothecin prodrug was synthetized and loaded in targeted nanomicelles. In vivo, nanoparticles distributed to a number of tissues, but payload was only transferred to VLA4-expressing cells, and preferentially to MMC surviving drug treatment. In mice with MM, combined treatment with nanoparticles and melphalan prolonged survival relative to high dose chemotherapy alone, and substantially reduced tumor burden relative to low-dose melphalan alone. No toxic effects were noted by clinical pathology, necropsy, or histology of organs sensitive to camptothecin derivatives. This suggests that nanotherapeutic targeting of drug resistant myeloma cells may be achieved with minimal to no toxicity by targeting drugs selectively to resistant cells, while lower doses of conventional drugs may be made more effective on the bulk of the tumor burden, further reducing the overall treatment-related toxicity. From a more technological standpoint, a deeper understanding of the biology of target cells and their relationship with their environment may help design more effective nanotherapeutics.

Ongoing studies aim at identifying the patient groups that would benefit the most from VLA4-targeted nanoparticles and characterize mechanisms of resistance to design corrective strategies. In collaboration with Dr. Shokeen (Radiology), theranostic implications of VLA4 binding in drug resistant cells are being addressed combining VLA4-based PET imaging and targeted treatment. In collaboration with the myeloma biobank and the Vij group, molecular patterns associated with high or low expression of VLA4 in patient cells and disease models are being investigated to find novel therapeutic targets and predictors of response in relapsing/refractory myeloma. Studies in collaboration with the Oncology Division aim at developing nanotherapeutics targeting surface proteins highly expressed in myeloma cells, which may reach a broader population of cancer cells when used as first-line agents.

Elizabeth Yanik

Orthopaedic Surgery

- Email: yanike@nospam.wustl.edu

Focus: Identifying and evaluating risk factors for rotator cuff disease, with an emphasis on genetic and occupational risk factors. Broad interest is in the interaction between genetic and non-genetic risk factors to influence musculoskeletal disease risk as a means of informing precision prevention approaches.

Dr. Yanik completed her PhD in Epidemiology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in 2013. From there she went on to complete a postdoctoral fellowship at the National Cancer Institute in the Division of Cancer Epidemiology and Genetics. During this time, her research focused on the development of malignancies in immunosuppressed clinical populations, specifically HIV-infected individuals and solid organ transplant recipients, using large population-based registries.

In 2016, Dr. Yanik joined the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at Washington University and transitioned to studying musculoskeletal epidemiology because of the opportunities to make unique contributions in an area with a relative dearth of active epidemiologists. Her current research focuses on identifying and evaluating risk factors for rotator cuff disease, with an emphasis on genetic and occupational risk factors. She is currently supported by an NIH/NIAMS K01 career development award to conduct research leveraging data available through the UK Biobank cohort. Her research team has linked a job exposure matrix to the UK Biobank to measure numerous dimensions of physical work, and demonstrated associations between these measures and incident rotator cuff surgery. This linkage will provide a tool for addressing numerous research questions about occupational risk factors for musculoskeletal disease in the future.

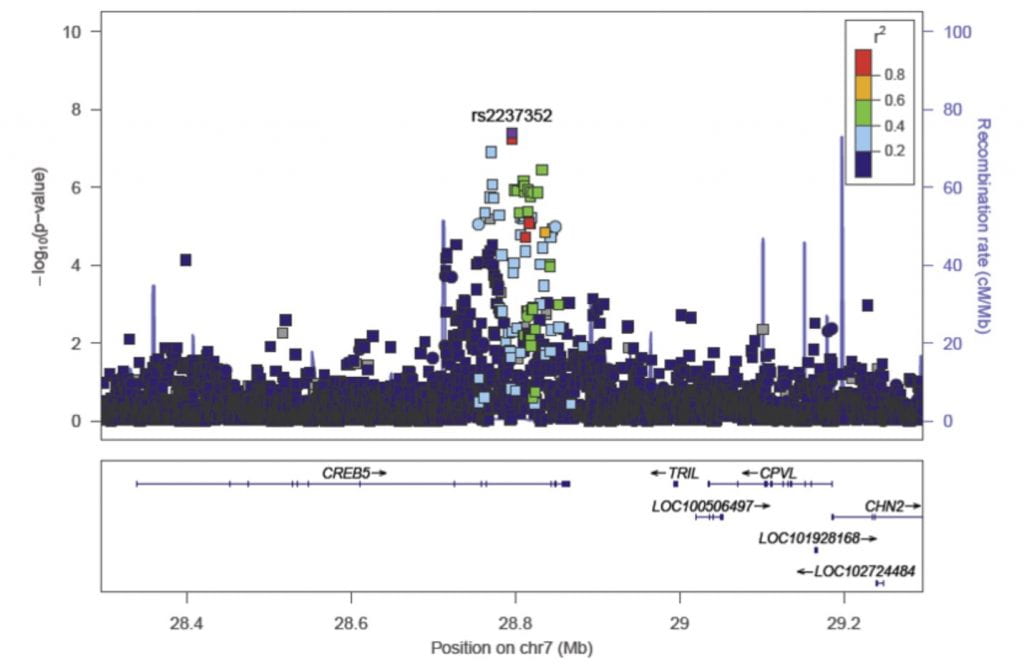

Her team has also used the UK Biobank to identify a novel variant in the CREB5 gene that is associated with increased risk of degenerative rotator cuff surgery (Figure). In collaboration with the Washington University Shoulder and Elbow service and with support from an OREF/ASES/Rockwood Clinical Grant in Shoulder Care award, Dr. Yanik is currently collecting specimens for genotyping degenerative rotator cuff disease patients in order to examine genetic determinants of tear size and age at clinical presentation. Ultimately, this work could help advance prediction of treatment outcomes and thus aid in informing treatment decisions.

Figure Legend. This LocusZoom plot shows the association (left y axis; log10-transformed p values) with degenerative rotator cuff disease surgery of single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) on chromosome 7. Genotyped SNPs are depicted by circles, and imputed SNPs are depicted by squares. Shading of the points represent the linkage disequilibrium (r2, based on the 1,000 Genomes Project Europeans) between each SNP and the top SNP, indicated by purple shading. Grey points in the plot represent the lack of linkage disequilibrium information between the index SNP (rs2237352) and the plotted SNP. [Yanik et al. JBJS 2021, doi: 10.2106/JBJS.20.01474.]

Allison Snyder-Warwick

Surgery

- Email: snydera@nospam.wustl.edu

Focus: facial reconstruction, facial nerve disorders, facial paralysis, facial clefts, cleft lip, cleft palate, ear reconstruction, microtia, reconstruction of obstetrical brachial plexus injuries, microsurgical procedures in children and adults.

Peripheral nerve pathology is devastating. To better understand the mechanisms of development, disease, and repair of the peripheral nervous system (PNS), all components of the PNS should be evaluated. Movement requires both neural input and muscle output. The Synaptic Glia and Translational Neuromuscular Research laboratory investigates the interface between nerve and muscle, the neuromuscular junction (NMJ). Led by Dr. Alison Snyder-Warwick, the lab specifically focuses on terminal Schwann cells, which are the specialized, non-myelinating glial cells located at the NMJ. The lab investigates the roles of terminal Schwann cells during development, disease, neural regeneration and muscular reinnervation, and aging. Currently, the lab is evaluating the role of a transcription factor they have previously found to be expressed in terminal Schwann cells, the intricacies of macrophage-derived VEGF signaling at the NMJ, and the implications of chronic denervation on NMJ recovery. The investigative goals are to identify the mechanisms of terminal Schwann cell function that may be manipulated into novel translational applications for clinical management of patients with peripheral nerve pathology.

Dr. Alison Snyder-Warwick is an Assistant Professor of Surgery in the Division of Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery, Residency Program Director, and Director of the Facial Nerve Institute at Washington University in St. Louis. Dr. Snyder-Warwick completed medical school, a research fellowship in Developmental Biology under the mentorship of Dr. David Ornitz, and surgical residency training all at Wash U. She then travelled to Toronto, Canada for specialized training in pediatric plastic surgery and pediatric microsurgery at the Hospital for Sick Children. While there, she performed translational nerve research under the guidance of Dr. Tessa Gordon and Dr. Gregory Borschel. At Wash U, her research mentors are Dr. Ornitz, Dr. Susan Mackinnon, and Dr. Aaron DiAntonio. Dr. Snyder-Warwick’s laboratory has received funding from the NIH, the Plastic Surgery Foundation, the Musculoskeletal Research Center, the McDonnell Center for Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology, and the American Association of Plastic Surgeons, and she recently completed her NIH Career Development Award (K08). She won the Bernard Sarnat Award for excellence in grant writing from the Plastic Surgery Foundation in 2017 and the inaugural American Society of Peripheral Nerve Traveling Fellowship for 2019. In addition, she has served as a research mentor for 2 postdoctoral research fellows (one with an NIH/NINDS F32 award), 6 medical students, and 2 undergraduate students. She received the Mentor of the Year Award from the Clinical Research Training Center at Washington University in 2018.

Matthew Goodwin

Orthopaedic Surgery

Focus: Targeting lactate transportation as a means of attacking cancers.

The Goodwin lab’s main interest is in metabolism – specifically lactate metabolism and its role in tumorigenesis. The Goodwin lab is focused on targeting lactate transportation as a means of attacking cancer. Cancer cells hold particular interest because of their unique metabolic history. Once described as unique because they were “lactate-producing” even when oxygen was plentiful (the “Warburg Effect”), many cancer cells have since been described as “lactate-consuming” (or “reverse Warburg”). The current debate as to whether a cancer cell produces lactate or consumes lactate as a fuel is further confounded by the confusion that has surrounded lactate metabolism in many medical specialties.

Once thought of as a metabolic waste product, lactate is now known to be a valuable and efficient fuel that can be transported and used throughout the body. In fact, lactate is preferred over glucose by most tissues. In contrast to glucose, lactate can move in and out of cells throughout the body via the ubiquitously expressed monocarboxylate transporters (MCTs). This is important because skeletal muscle and liver both store glucose as glycogen. While the liver can release glucose from glycogen into the blood, skeletal muscle is unable to do so. However, muscle is equipped with receptors that bind catecholamines and lead to the breakdown of glycogen to lactate, which is then driven by diffusion down its concentration gradient to the blood, where it can circulate to tissues in need. Thus, substrate from muscle throughout the body can be quickly and efficiently mobilized in times of need. Lactate enters cells, is converted to pyruvate, and is oxidized in the mitochondria. This robust and flexible system of substrate shuttling makes lactate the ideal system for tumor cells to hijack. Tumors of all types certainly appear to rely on lactate to some degree. In some cases they appear to be using lactate as a fuel (Goodwin et al., Cancer Cell 2014), while in other instances they appear to be producing lactate. Evidence for both exists (depending on the tumor type and condition) – inhibiting lactate transport seems to have an effect on tumors in both situations. And for some cancers, evidence exists that they do both! This discrepancy is mainly due to the profound influence the tumor microenvironment has on tumor cell behavior, and the difficulty in replicating the tumor microenvironment in the lab.

To that end, our lab focuses on defining the metabolic behavior of a tumor cell by a variety of methods and unique laboratory techniques, and then targeting that unique behavior. For example, current work is examining the role of MCTs in osteosarcoma metabolism. For many years tumor treatment was limited to radiation, chemotherapy, and surgery. We have now entered the era of targeted treatments, and targeting tumor metabolism holds the potential for new, more effective, and less toxic cancer treatments.

A secondary interest of the lab is the role of lactate in intervertebral disc (IVD) metabolism and degenerative disc disease. IVDs and tumors represents the “extremes” of metabolism. Tumors are often hyper-vascular, while discs are largely avascular. This contrasting metabolic behavior represents opposing ends of the spectrum of human tissue, providing a unique insight into basic principles underlying metabolism. However, disc behavior also mirrors tumor behavior in many ways. The nucleus pulposus represents a relatively avascular core at the center of a complex 3D microenvironment. Given this, IVDs function much the way tumors do, by relying on lactate shuttling to coordinate metabolism. Early work has shown that inhibiting MCTs in discs leads to rapid IVD degeneration. By studying the role of lactate as a nutrient in disc metabolism and the complicated IVD microenvironment, we are able to move closer to treatments for both cancers and many spinal pathologies, conditions that affect millions of people.

Goodwin Lab Members (from left): Mieradili Mulati, Md, PhD (Post-Doctoral Fellow), Shambhavi Bhagwat, MS (PhD Student), Kya Vaughn (Post Graduate Asst.), Evan Polsky (Undergraduate Asst.)

2020

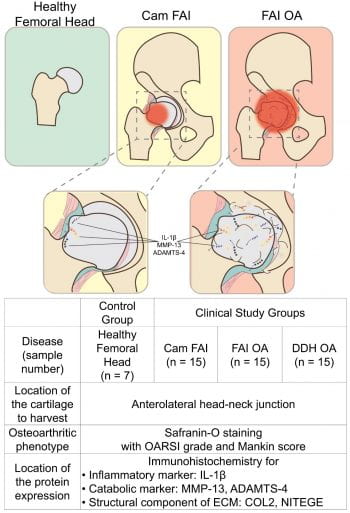

Jie Shen, PhD

Orthopaedic Surgery

- Phone: 314-747-2567

- Email: shen.j@nospam.wustl.edu

Focus: cartilage, bone repair, skeletal development, cancer and inflammatory diseases of bone.

Dr. Shen completed his doctoral research in osteoarthritis at University of Rochester in 2012. The same year, he joined Dr. Regis O’Keefe’s laboratory as a postdoctoral researcher, and expanded his research to bone fracture repair, particularly the importance of the DNA methylation in mesenchymal stem cells. In 2018, Dr. Shen was promoted to Assistant Professor in the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery at Washington University in St. Louis. His current research interests span aspects of bone and cartilage research, and are mainly focused on injury, repair and regeneration of musculoskeletal tissues with the goal to understand the progenitor cell population, signals, and role of disease and aging on tissue injury and regeneration at the cellular and molecular level. One of the focuses in the Shen lab is to study the mechanism of epigenetic factor, DNA methyltransferase 3b in fracture nonunion under inflammatory diseases, which is a totally novel field for the bone and cartilage studies. This work has been recently funded with an R21 and two R01s.

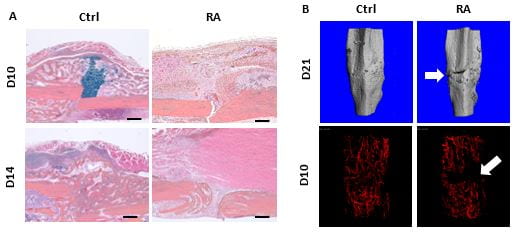

Fracture nonunion is an exceedingly challenging clinical problem with limited and mainly invasive therapeutic interventions. It is more prevalent in patients experiencing chronic inflammatory conditions, including diabetes and rheumatoid arthritis (RA). Clinical studies have illustrated that chronic inflammation adversely affects progenitor cell differentiation and neo-angiogenesis in patients, and in turn results in the failure of bony callus formation and develops fracture nonunion. Although significant advances have been made in defining the affected cell differentiation and angiogenic process for potential pharmacologic targets, there is still an unmet clinical need for new therapeutic approaches for fracture repair and nonunion treatment, especially for older patients those with comorbidities such as diabetes and RA. Indeed, serum transfer-induced RA (K/BxN) mice displayed fracture nonunion with absence of fracture callus, diminished angiogenesis and fibrotic scar tissue formation (Fig. 1), leading to failure of biomechanical properties, which represented the major manifestations of atrophic nonunion in clinic. However, a gap of knowledge remains regarding the downstream targets of this phenomenon.

To bridge this gap, we have focused on epigenetics, especially DNA methylation, which has emerged as a critical modulator in various cells, under inflammatory condition such as RA. Indeed, recent epigenome studies from fracture patients revealed differential methylation loci in human cells, suggesting that DNA methylation is involved in fracture repair process. Importantly, our preliminary data show that the epigenetic enzyme Dnmt3b is highly expressed in fracture callus during fracture repair and Dnmt3b is the major DNA methyltransferase (Dnmt) responsive to cytokines in progenitor cells and chondrocytes. Mechanistically, 1) progenitor cell differentiation defect mediated by inflammation and Dnmt3b LOF coincide with upregulation of Rbpjx in progenitor cells and Rbpjx inhibition can restore differentiation capacity in vitro; 2) angiogenesis defect mediated by inflammation and Dnmt3b LOF coincide with downregulation of OPN (Osteopontin) and CXCL12 (C-X-C Motif Chemokine Ligand 12) and exogenous OPN and CXCL12 can restore angiogenesis capacity in vitro. In collaboration with Dr. Jianjun Guan, we propose to develop potentially therapeutical approaches for fracture nonunion treatment via delivery of growth factors (OPN and CXCL12) and genetically modified progenitor cells (① feedback-controlled anti-inflammatory stem cells with Dnmt3b overexpression and ② stem cells with locally DNA methylation modified Rbpjx into fracture site by PCL scaffold.

Additional information about the lab is available on our website:

https://orthopaedicresearch.wustl.edu/labs/jie-shen/

Kevin Middleton

University of Missouri – Pathology

Focus: the integrative biology and evolution of vertebrate “locomotor tissues” including not only bones and muscles but also feathers and wing membranes.

Dr. Middleton joined the Department of Pathology & Anatomical Sciences in the University of Missouri School of Medicine in 2012. Originally trained as a paleontologist and functional anatomist, he completed his doctoral research at Brown University avian foot evolution. He remained at Brown as a postdoctoral research associate, studying the aerodynamics of bat flight and the mechanical properties of bat wing bones. An NIH NRSA Postdoctoral Research fellowship at the University of California, Riverside and Brown motivated a switch to using mouse models to study the genetic and plastic responses to selection for high levels of voluntary activity on the musculoskeletal system. Past projects in the lab have included penguin evolution, the effects of atmospheric oxygen on skeletal ontogeny in alligators, and the evolution and biomechanics of bird heads. Recently, we began developing non-linear Bayesian models to estimate growth trajectories in the human head. Despite these varied interests, the main focus of the lab is the interplay between genetic background and lifetime voluntary activity in determining skeletal structure & function.

We study mice that have been artificially selected for high levels of voluntary wheel activity as a model organism to explore the diverse effects of high levels of voluntary exercise on musculoskeletal ontogeny, form, and function. For over eighty generations, these mice have been bred for increased voluntary activity and run nearly three times farther than randomly bred controls, often more than 25 km in one night. Such repetitive loading of the skeletal system provides a unique opportunity to study the interaction between genetic background and activity on bone growth, form, and function. Work has focused on the response of the skeletal system to both long-term selection and acute exercise. Initial studies focused on morphological changes associated with either artificial selection or exercise, or the combined effects of the two, with the goal of addressing fundamental questions about the skeletal response to exercise and changes to the underlying genetic landscape. Several studies using both traditional morphometric techniques and fine-scale micro-computed tomography (µCT) revealed significant skeletal differences between selected and control mice. Two recent projects have been enhanced by working with the Musculoskeletal Research Center’s Structure and Strength Core.

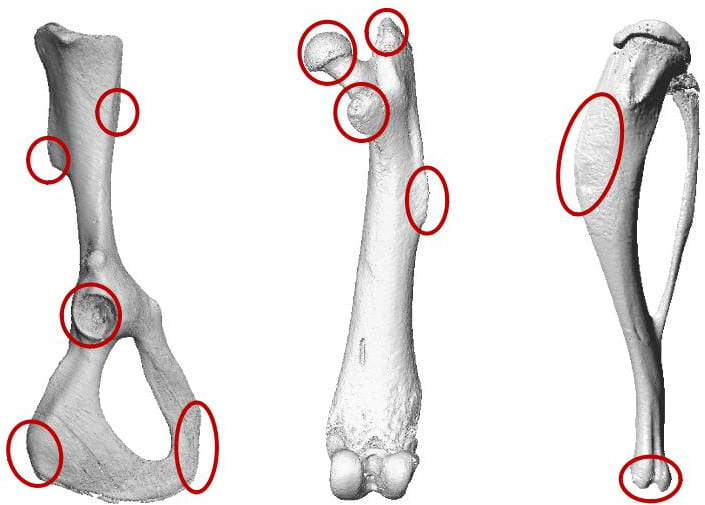

In the first of these projects, we compared pelvis and hind limb shapes between randomly bred control mice and those artificially selected for high activity (Figure 1).

In the pelvis and proximal femur, we find many areas of significant morphological divergence, which are associated with altered gait kinematics and kinetics in selected lines. There appears to be a proximodistal gradient, with change concentrated in the pelvis and hip, with fewer differences observed in the tibia. In a second project, we compared the evolved cranial morphology in exercise-selected mice to that of controls, which shows distinct patterns of change in the neurocranium vs. the viscerocranium (Figure 2).

Exercise selected mice show significantly expanded neurocranium and posterior skull, with wider nuchal plane and foramen magnum. In contrast, these mice have significantly reduced viscerocrania, including a smaller overall face and shorter, narrower palate. In additional to these evolved responses, both lines show unique patterns of plastic responses to exercise. Future research will investigate the ontogenetic patterns and mechanistic basis for these differences.

Additional information about the lab is available on our website: https://www.middletonlab.org/

2019

Clarissa Craft

Cell Biology & Physiology

Focus: the composition of the extracellular matrix (ECM) influences the biochemical and mechanical properties of the cellular microenvironment, and whether the ECM could serve as a therapeutic target for combating diabetes.

Dr. Craft completed her graduate work in cancer drug discovery at Northwestern University’s Feinberg School of Medicine in 2007. The same year, she joined the Department of Cell Biology and Physiology at Washington University as a postdoctoral fellow in the laboratory of Dr. Bob Mecham. During her fellowship, Dr. Craft investigated extracellular matrix (ECM)-mediated regulation of TGFß within the skeleton. In 2012, Dr. Craft was promoted to Assistant Professor in the Department of Cell Biology and Physiology. Early in her independent career, Dr. Craft was funded by the American Diabetes Association to define the role of the ECM in adiposity and metabolic disease. During this time, she found that loss of a single ECM protein, MAGP1, was sufficient to predispose mice to metabolic syndrome (obesity and diabetes), pathologic bone marrow adipose tissue (BMAT) expansion, and bone fractures. The finding that diabetes was linked to bone fragility and altered BMAT adipocyte function led to a collaboration with Dr. Erica Scheller. In response to the success of their collaboration, in 2016 Dr. Craft transferred to the Division of Bone and Mineral Diseases to create a novel joint laboratory with Dr. Scheller which investigates the relationship between nerves and bone, with current emphasis on neuropathy and skeletal metabolism in diabetes. The lab’s research in bone marrow adiposity (BMA), diabetic neuropathy, and skeletal ECM were recently highlighted through oral presentations at the 2018 BMA Society meeting in Lille, France and the 2018 ASBMR meeting in Montreal, Canada. In her spare time, Dr. Craft enjoys spending time outdoors with her husband and children at their farm in Sullivan, Missouri.

For more information about Dr. Craft’s research interests, please visit the lab’s website:

https://bonehealth.wustl.edu/research/laboratories/scheller-and-craft-lab/

Assistant Professor of Orthopaedic Surgery

Hand & Microvascular Surgery Service

The Orthopaedic Nerve Research Lab is a collaborative effort between Dr. Christopher Dy and Dr. David Brogan. Over the past two years, the laboratory has been focused on translational and epidemiologic research regarding complex peripheral nerve injuries. Dr. Dy has received funding from the NIH to explore the utilization of qualitative research methods in describing the psychosocial effects of brachial plexus injuries on patients. His previous work has also focused on understanding the epidemiology of these severe injuries to better understand injury patterns.

Dr. Brogan’s focus is on translational research to better improve the diagnosis of nerve injuries in the operating room. He has received funding from the American Foundation for Surgery of the Hand to evaluate the application of laser Doppler blood flow technology through the diagnosis of peripheral nerve crush injuries. The lab also works closely with Dr. Samuel Achilefu in the Optical Radiology Lab. The current work explores the utilization of near-infrared optical probes to better understand the cascade and sequence of events that occur surrounding a peripheral nerve injury. Our hope is to eventually develop tools that can be utilized with existing equipment in the operating room to assist with image-guided nerve surgery. The lab also has ongoing collaborations with the Department of Genetics as well as the Department of Neurosurgery. Dr. Dy and Dr. Brogan are committed to continuing their work to hopefully improve the diagnosis of nerve injuries, as well as mechanisms for better surgical treatment and the aftercare of patients affected by these life-altering injuries.

Research Associate Professor of Medicine

Division of Geriatrics & Nutritional Science

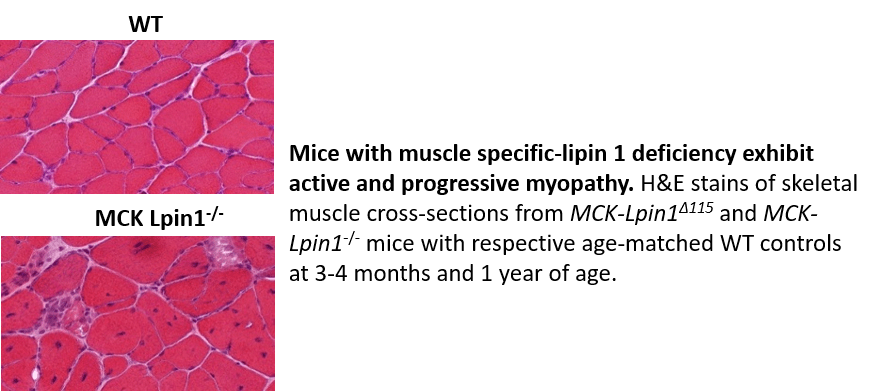

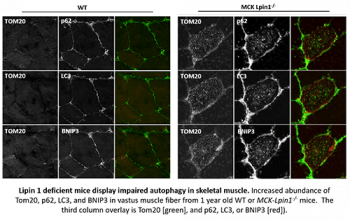

The Finck Lab is interested in understanding the regulation of intermediary metabolism in a variety of tissues, including skeletal muscle. For many years, we have been interested in the lipin family of proteins (lipin 1, 2, and 3). Lipins are intracellular proteins that primarily act as lipid phosphatase enzymes in the pathway of triglyceride synthesis. Interestingly, these proteins can also translocate to the nucleus to directly regulate gene expression by interacting with DNA-bound transcription factors that control the expression of metabolic enzymes. Thus, lipin proteins can control metabolism at multiple regulatory levels by affecting gene expression and by their effects as phosphatase enzymes.

Lipin 1 is the lipin isoform that is most highly expressed in skeletal muscle. Recent work has demonstrated that rare mutations in the gene encoding lipin 1 in humans (LPIN1) lead to recurrent, episodic rhabdomyolysis that manifests mainly when these patients are children. In collaboration with Dr. Robert Bucelli, who has identified patients with LPIN1 mutations in the St. Louis area, we characterized a novel mutation in lipin 1 and teased apart the effects of several disease-causing mutations on the activities of the protein. While many mutations were complete loss of function, it was determined that some of the mutations caused a loss of enzymatic activity of lipin 1 protein without affecting its ability to regulate gene transcription. This suggests that defects in lipin’s lipid phosphatase activity leads to pathologic changes that explain the etiology of rhabdomyolysis in these patients.

To better understand this, Dr. George Schweitzer in the Finck group created novel mice with skeletal muscle-specific knockout of lipin 1. While outwardly normal, skeletal muscle of the knockout mice exhibited a chronic myopathy with ongoing muscle fiber necrosis and regeneration. These mice also exhibited accumulation of the lipid substrate of lipin 1, phosphatidic acid, in muscle. Additionally, lipin 1-deficient mice had abundant, yet abnormal mitochondria likely due to impaired autophagy. Phosphatidic acid suppresses autophagy by a variety of mechanisms, including by stimulating the activity of the mTOR kinase signaling cascade, which can be targeted by pharmacologic means.

While these mice do not completely phenocopy the episodic nature of patients with the human LPIN1 mutation, these data suggest that mice lacking lipin 1-mediated PAP activity in skeletal muscle may serve as a model for further exploration of the mechanisms by which lipin 1 deficiency leads to myocyte injury. We also hope to use these mice to test potential therapeutic or preventative approaches. Lastly, the lab is also interested in determining whether lipin 1 deactivation in other more common forms of muscular dystrophy may contribute to the progression of those diseases by similar mechanisms.

Professor

Department of Mechanical Engineering and Materials Science

The Polymers, Interfaces, and Regenerative Medicine lab led by Prof. Jianjun Guan at the Department of Mechanical Engineering and Materials Science is interested in biomimetic biomaterials synthesis and scaffold fabrication; bioinspired modification of biomaterials; injectable and highly flexible hydrogels; bioimageable polymers for MRI and EPR imaging and oxygen sensing; mathematical modeling of scaffold structural and mechanical properties; stem cell transplantation; and bone, skeletal muscle, skin, and cardiac regeneration.